Human evolution does not roll itself out at fibre-optic speed. Quite on the contrary, we humans evolve extremely slowly with unrecognisable differences from generation to generation. Indeed many scientists across the board classify our neural structures still as a “stone-age brain”.

What if it’s not so much that we are still club-swinging, lust-driven and grunting, but that we have stayed with some of the stone-age principles because they make us happy and make sense to us? For example, as Malcolm Gladwell cites in his latest book ‘David & Goliath’, the activities that result in the most happiness for humans are simply walking and creating something with one’s hands.

EVOLUTION ACCOMPLISHED

In terms of social interaction and engagement, it seems our brain has managed the slow transformation from nomadic tribes to village settlements. We have expanded our sense of belonging to include place as well as our social group. Still, the times when we were nomads cover about 90% of human history. So from that perspective, settling in a place and being able to cognitively process that is a recent development. On top of that, the world around us is growing more and more challenging. We are living in denser environments, are exposed to ever broader connectivity, and the pace of change is picking up.

The question is: will the human brain be able to adapt? What happens to us and to our behavioural patterns once we operate in an urban landscape at 500 mbps and have performance measured in created economical growth?

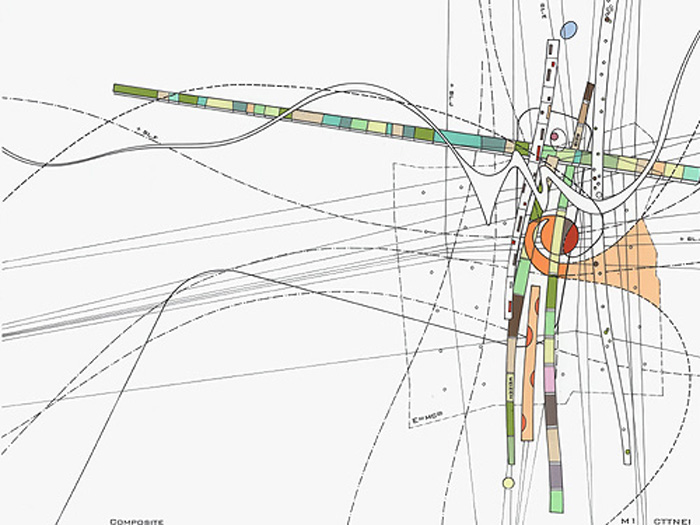

Petra Kempf’s ‘You are the City’ publication. Source://www.archdaily.com/36404/you-are-the-city-petra-kempf/

CREATING YOUR OWN VILLAGE

There are numerous indications that we follow the principle of sticking to what makes us happy or comfortable. And if we can’t stick to it, we adapt it to fit the new contexts we find ourselves in. Observing how humans form and engage in communities, we propose that the brain still operates on the village scale. Consider this:

Firstly, the size of our social networks: if Facebook can serve as an indicator of social activity, the average is about 130 friends and only rarely more than 800. That is about the size of a small village settlement and confirms ‘Dunbar’s number’. This figure is based on British anthropologist Robin Dunbar’s research in social- and neuroscience, stating that the limit we humans have for forming and maintaining stable relationships is rooted in our neural build-up. The theory is that the size of the neocortex determines our cognitive limit for social relationships. In the case of humans, it is 148.

Secondly, as the pace of modern life is sped up by digital technologies, a whole slow movement has developed in response. There is slow food, slow transportation, and slow activities such as gardening, yoga, tai-chi are on the rise.

Thirdly, the city-amenities paradox: Even when located in large and complex cities, we have an urge to define our village within that. We are thrilled to locate “our bakery”; the “best route to work”; “nicest restaurant”; “favourite park”; “coolest street”. The city thus becomes a full colour palette for everyone to set the tone of their personal village. This means that instead of being constantly confronted with choices, we select a number of places, which define our “village” within whatever setting we are in.

WHAT’S YOUR SCALE?

These are only a couple of many features which suggest that our brain isn’t a contemporary capitalistic urban beast that processes vast amounts of information equally, but something more selective that develops at a hesitant pace. Maybe the urban developments we plan would result in more liveable spaces if the village scale would be everyone’s scale.

Sources:

//www.statisticbrain.com/facebook-statistics/

//www.ted.com/talks/malcolm_gladwell_the_unheard_story_of_david_and_goliath.html

//www.forbes.com/sites/knowledgewharton/2013/12/05/272013/

//connection.sagepub.com/blog/2013/11/07/robin-dunbar-on-dunbar-numbers/

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunbar%27s_number