It has been over a month since Machines Room said goodbye to our Hello Shenzhen Maker in Residence, Kang Cheng, but far from being a final farewell, the exchange programme has proven to be only the start of what we hope will be a long-term collaboration between our East London makerspace and Kang and his team at Esun makerspace in Shenzhen.

During his residency Kang worked on a project in collaboration Disrupt Disability, designing and prototyping a core ‘hub’ for a wheelchair.

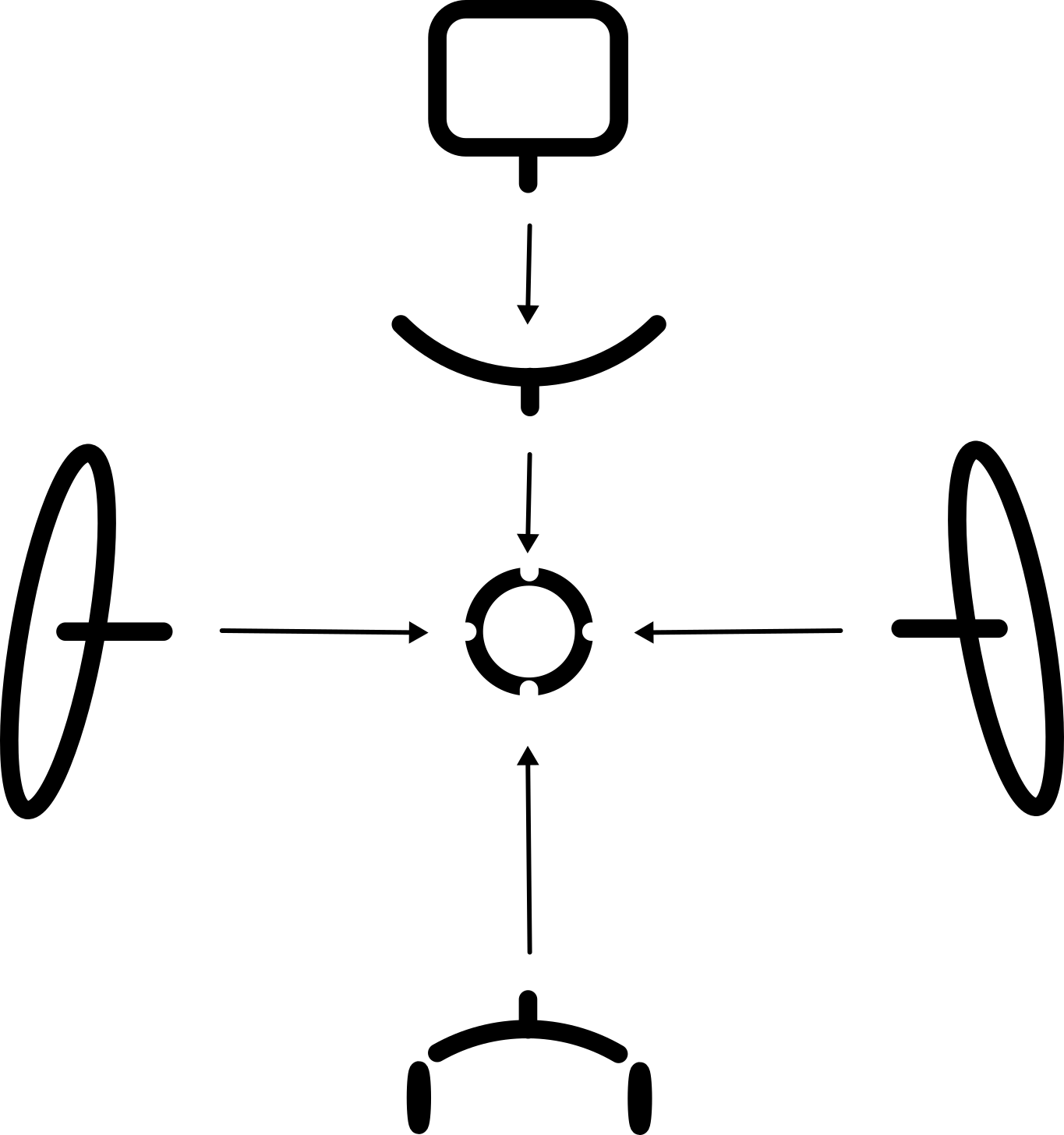

Rachael’s brief for Kang was to design and develop a core ‘hub’ for a wheelchair, above.

Disrupt Disability have been Makers in Residence at Machines Room since June 2016, and are working on a project exploring how makerspaces can be used to connect wheelchair users directly to the design and manufacturing process of making wheelchairs.

The concept of a wheelchair ‘hub’ was the idea of Disrupt Disability’s Founder Rachael Wallach, who wanted to explore how a single component with a set of standardised interfaces could be used to enable wheelchair users to customise and create individual wheelchair components, e.g. the footplate.

Rachael’s objective is to give wheelchair users greater control over both the form and function of their chair, and create the same amount of choice for wheelchair users (or wearers) over their wheels as glasses wearers have over the look and function of their glasses, where you can choose a frame that reflects your style.

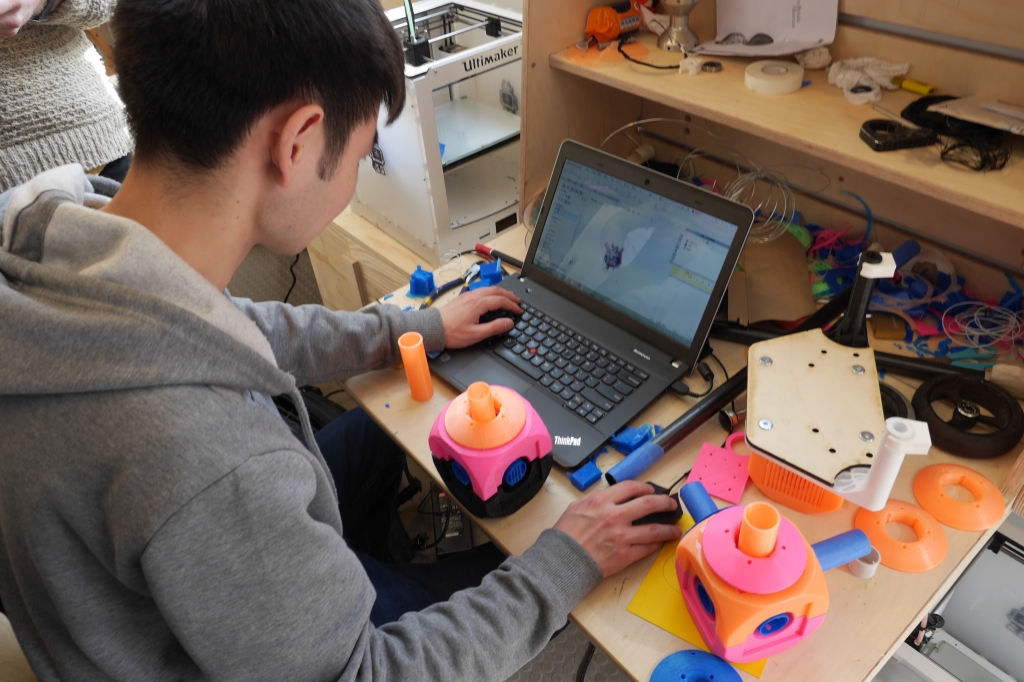

Kang’s 3D printing expertise meant that he was able to work closely with Rachael to rapidly prototype designs, working in sprints. Towards the end of the first week, Kang had invented a quick release push and twist mechanism that would enable the wheelchair user to easily connect different components to the wheelchair hub. The design for the mechanism was based on the quick release mechanism already in use for wheelchair wheels, which enables wheelchair users to remove their wheels from the frame of their chair.

This was the real breakthrough moment of the project, as the mechanism means that the wheelchair user could easily interchange different components, completely changing the form and function of their chair – for example by changing the footplate or seat.

One of the highlights of the residency was a visit from Kang’s colleague Rongsheng Zhang and Dan Chambers from Draft wheelchairs. Dan showed us how wheelchairs are measured and made using traditional manufacturing techniques – each length of tubing has to be bespoke bent for each individual person. We learnt about how there are variables based on the individual’s body size, but also their disability. For example, someone with less leg control might want higher tubing for their footrest to give more support.

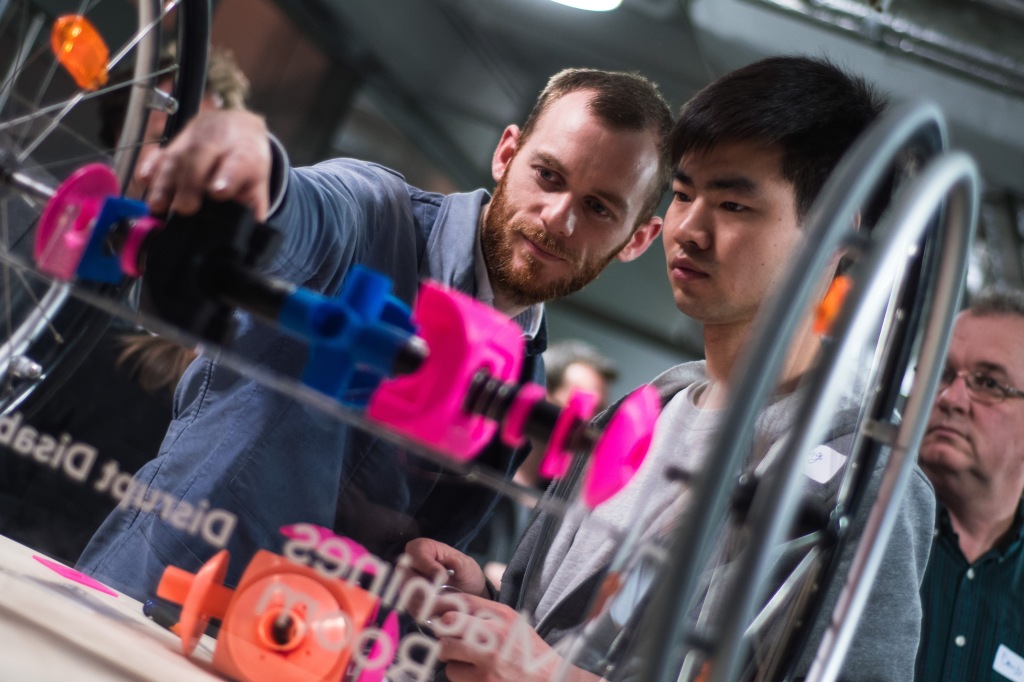

Kang, Dan and Rongsheng at Machines Room

We also learnt that sizing can change due to the preference of the wearer. The one we were testing has a seat positioned behind the axle, making it ‘tippy’. This makes it easier to get up kerbs and small steps. But it also means that you need to have more core control in order to tip and not fall out the back of the chair!

Rongsheng and Kang were then able to talk to Dan about 3D printing and digital fabrication, and identify different materials that could be used to give different functionality. Together, they were able to estimate the size of the 3D printed elements in order to provide the requisite strength, and reiterated Kang’s design to take account of this level of functionality. The collaboration enabled us to begin to understand how a functional wheelchair could be produced in a makerspace.

When the changes were presented to Rachael, she explained that most traditional wheelchair designs start with a chair and then add on wheels. This makes sense if you are designing a medical device for moving or pushing someone around, but not for wearable wheels that people can use to propel themselves.

One of the opportunities that makerspaces and digital fabrication presents is that it could enable you to design and manufacture a wheelchair that reverses this process, to prioritise form over function and design a chair that puts the wheel user at the forefront of the design process.

A modular system would allow a wheelchair parts to be interchanged and repaired, much like a bike, or worn with style, like glasses. Therefore, while to some extent, function is important – you need to be able to get from A to B. But your wheels don’t just need to work, they need to work for you. A good analogy is to look at footwear – ‘shoe wearers’ might choose to wear impractical or even uncomfortable shoes because they suit their outfit or to express their identity. Why shouldn’t wheel wearers have the same choice.

Kang’s final design for the modular hub, aims to maximise the wheel wearer’s control over the function and form of their chair. All wheelchair components – seat, backrest, rear wheel axle, castor fork and footplate – connect to the hub. Standard connectors enable wheel wearers to choose and interchange differently designed components and customise the chair to their needs. One stand-out feature is the quick release button connecting mechanism, which enables different wheelchair components to be easily interchanged and ‘clicked’ into place with the press of a button.

Kang’s final design for the hub, with quick release mechanism

“For me the light bulb moment was seeing the quick release mechanism that Kang designed in action. We needed a system that enables users to interchange different wheelchair parts but until I saw his design working I never imagined that it would really be as easy as the press of a button.” – Rachael

One of the biggest revelations during the project was how Kang’s design could facilitate a shift in the way wheelchairs are designed and made so that form, as well as function, is a priority that can take precedent in the design.

Next steps

After he returns to China, Kang would like to continue the project where it can benefit from the resources of Shenzhen and his Zealfull factory. Kang also introduced the team to his colleague Dr Rongsheng Zhang who is moving to London and can help with materials.

For Disrupt Disability, the Hello Shenzhen programme has provided an incredible opportunity to connect to makers in China. The programme has provided the team in the UK with a far better understanding of the opportunities presented by taking the project global.

Kang’s final design reflects views from the Disrupt Disability community about choice over form and function – giving wheel wearers the ability to easily customise how their wheels look and work. Kang and Rachael envisage that the “hub” and the relevant “connectors” would not themselves be customized to the individual, but that they would be lightweight and could be mass produced. Working together, they can see opportunities to continue to develop and then manufacture the hub so that the idea of the modular wheelchair can become a reality.